05-Apr-2024, 11:50 p.m., Knoxville, Tennessee

“Clouds are the enemy of eclipse observing. No place along the eclipse path is immune to the threat of clouds.” -Totality by Mark Littmann and Fred Espenek

I lay sideways in bed, propped up on my elbow. A book on the sheets beside me is open to a chart of cities. Phone in hand, I frantically switch between weather app and GPS.

Bloomington, Indiana—Totality: 4min 2sec —5 ½ hour drive—Partly Cloudy

Hot Springs, Arkansas— Totality: 3min 36sec—8 ½ hour drive—Partly Cloudy

Akron, Ohio— Totality: 2min 49sec—7 hour drive—Mostly Cloudy

Erie, Pennsylvania— Totality: 3min 42sec—8 ½ hour drive—Mostly Cloudy

Fuck it.

Dallas, Texas— Totality: 3min 48 sec—12 ½ hour drive—Sun and Clouds mixed with a slight chance of Thunderstorms

My heart races.

Texarkana—No, that’s only 2 minutes 28 seconds of totality, and it’s closer to Arkansas, where the chance of clouds is higher.

I briefly think of waking my fiancée, Camryn Crowe, to express my frustration and tell her we may just need to drive to Dallas. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. What’s another 14 hours in the car anyway?

No. Calm down. It’s only a total eclipse. There will be another in 2044. Bloomington it is.

21-Aug-2017, 2:00 p.m., Maryville, Tennessee

I sit on my back porch, moping. Tennessee had caught eclipse fever. On average, an eclipse only passes through a city once every 345 years, so it was pretty justified. The news seemed to bring it up every day. People were calling in from work; buying eclipse glasses from gas stations and libraries, and when those ran out, they were buying welding helmets from Home Depot, and when those ran out, they were buying cardboard boxes and aluminum foil from Walmart to make their own box pinhole projectors.

And there I was, having none of these things. Sure, I’d heard it was coming, but by the time I took it seriously, there were none left. Why take it seriously? There will be another in about 345 years.

My dad swings open the door.

Our neighbor has an extra pair of glasses, he says.

I sprint outside and thank her profusely. My dad and I take turns looking through them at the eclipse—still in the partial phase. It looks silly through the glasses. Like some sort of little projection, or when you hold your fingers in front of a flashlight. Then, we try doing the thing the news explicitly told us not to do, and stare at the sun without the glasses.

God, it seems worse than glancing at the sun on a regular day. Who the hell could do that for the entire eclipse? It didn’t even look any different than glancing at the sun on a regular day, the light being so bright. I put back on the glasses. That’s better.

And then the moment came. Totality. The sky darkened. The air got cold. Cicadas chirped, frogs ribbited and birds went to their nests. I take off the glasses and look up.

And you know what? I can hardly remember what it looked like.

Why do people chase eclipses?

There was no exact moment when the question entered my mind. It just sort of . . . crept in there. I do know where it came from, though. It was my Science Writing as Literature class at the University of Tennessee. The professor, Mark Littmann, was crazy about the eclipses. He chased them, wrote several books about them, and made us read stories about maniacs who’d do the same. I remember reading one about a motley crew of deluded psychopaths who traveled all the way to the Middle East just for a few minutes of totality. What the hell was that about? I’d seen one. It didn’t seem that special to me.

For months curiosity built in the back of my mind. What’s the big deal to these people about the moon moving in front of the sun? What did it mean to them? I had to find out.

07-Apr-2024, Around 11:00 a.m., Bloomington, Indiana

We’ve been driving since 4:00 a.m., but finally, we see the sign, “Lights Out At Loesch Farm.”

The sun beams through thick white clouds and the damp smell of impending rain as we drive up the gravel road toward a canopy. There, a cardboard sign written in Sharpie suggests that we check in. A tall, tan, cool-lookin’ dude in sandals and a rain jacket comes jogging down the muddy field. He introduces himself as Josh, gives us a map, and tells us they’ve been letting people set up camp pretty much anywhere they want.

Where are you two from? Josh asks.

Knoxville, Tennessee, I say.

Awww man that’s so cool. We’ve had people from Arkansas, Tennessee, Texas—all over! He exclaims.

I laugh and express my wish that the weather clears up.

I don’t have high hopes, but we’re gonna have a good time either way, Josh replies, heading back up the hill.

Camryn drives her sedan to the end of the gravel road next to some porta potties. The field in front of us is covered in a decent layer of mud.

After some debate about whether we can make it, Camryn executes a three-point turn. She carefully backs her car to the end of the road and, eyes fixed on her backup camera, punches the gas, rocketing the car backward through the field, and slinging dirt all over the side of her car. Through the motion blur, I manage to make out a young couple sitting in lawn chairs next to a school bus-turned RV. The guy is tickled to death at the sight of us; he bounces in his chair and gives us a thumbs-up.

As we set up our tent, I intermittently glance up at the sky. During a total eclipse of the sun, the temperature drops approximately 10 degrees Fahrenheit, which can actually dissipate some higher-up wispy clouds. It’s sort of like steam rising from boiling water; eventually, the drop in pressure and lower temperature turns the vapor into clear air. God, I hope it’s not too cloudy tomorrow.

With our campsite set up, we pile back into the car and head forward through the rolling hills, past the hippie RV, and across the gravel road, looking for a place to park. Beside the stage is the man himself, the owner of Loesch Farm, wrapping caution tape around steel posts to create a makeshift fence.

His name is Jeff Mease, and if you called him an average hippie, you’d only be half right. Sure, he’s got the ponytail, the colorful cloth sack slung over his shoulder, the Birkenstocks, and he sips on Kombucha while he talks to you, but this dude is anything but average. Take a quick glance at his business card and you’ll see why.

Jeff is the founder and CEO of One World Enterprises, the parent company of nine different food service businesses located in Bloomington. They all sprang from a single chain he founded in 1982 called Pizza X, which now has five locations.

A lover of gardening, Jeff bought Loesch Farm from another businessman during the real-estate crash in 2009. Over the years, Jeff tried his hand at raising various livestock around the farm, including Asian water buffalo, but it never worked out.

“I got a lot of respect for real farmers,” Jeff said. “I wouldn’t even call myself a gentleman farmer; I’m sort of a hack. I’m not trying to make money on growing stuff. The land’s already appreciated. It’s made money—in a way. And that’s plenty. So the rest we can just kinda do for fun.”

With 69 acres of land and nothing to grow on it, Loesch Farm became Jeff’s place to have fun with his friends: throwing parties for the fall equinox and summer solstice, and hosting small concerts for the local community.

In 2017, Jeff heard about the eclipse that passed through the US from South Carolina to Oregon. With a bit of research, he realized the 2024 eclipse would pass right over his land and he decided it would make the perfect party. An idea that was further cemented when he noticed that the local hotels were jacking up their rates for the occasion, some charging upwards of $1,000 per night.

“I can’t stand for that,” Jeff said. “So, we made an event, and just a week ago I put it up on Hipcamp and made it $25 a night, just to make it easy for people. This isn’t really about making a profit. I’m fortunate and privileged because I have businesses that make money, and then I can do things like this, which are a little bit more like a dance with the cosmos, where you can make something that people enjoy and they feel lucky that they found it. That’s magic.”

07-Apr-2024, from around 8:00—10:30 p.m., Loesch Farm

We sit in the dark with our new friends by their school bus RV. The weather has taken a turn for the worse, and I’ve stopped trying to keep the rain from pouring into the pot of soup cooking over the campfire. Only Camryn has the genius idea to use an umbrella. As for the rest of us, we just sit in the rain which soaks through our warming layers and into the lawn chairs.

Their names are Thomas Schutzman and Brookelyn Stumler and they didn’t want to live a traditional life of mortgages and houses.

“The original idea was to buy the bus and live in it,” said Thomas. “But that didn’t end up happening, so now we just use it more like, on weekends and road trips and stuff.”

Together, Thomas and Brookelyn learned electrical work, tile work, welding and carpentry to transform the retired school bus into a fully-fledged home, a process that took about three years. Due to job constraints, however, they ended up buying a little house in southern Indiana, where they try their hands at farm work and sustainable living.

When they heard about the eclipse, the couple knew they had to go check it out.

“I mean it’s crazy that we’re just floating on a rock through space right now, so being able to experience a celestial event is really sick,” said Thomas. “A lot of people get stuck in the day-to-day of life and they don’t take a second to actually just look at what’s happening.”

We spend the rest of the night in the pouring rain drinking and swapping stories about everything from science to music festivals to how many times we’d shat in the woods. When someone leaves to use the porta-potties, they have to shake a puddle out of their chair when they get back, a process that doesn’t make much difference.

I’ve been checking my weather app, and it’s looking better and better for tomorrow, said Thomas.

I know, said Camryn, I’ll take all the wind and rain in the world tonight if it means all this blows away.

08-Apr-2024, around 11:30 a.m., Loesch Farm

Blow away it did. Camryn and I finish packing the car under a blue sky and full sun. The humidity has become so thick that I strip down to an unbuttoned shirt and a pair of ratty shorts that Thomas was nice enough to give me.

The excitement is building in the crowd, which now consists of a couple hundred people as cars continually pour into the giant muddy field. We take our places in front of a stage, where local band Atom Heart Mother plays the entire album Dark Side of the Moon, by Pink Floyd to a crowd of hippies, children, tourists, photographers and amateur astronomers.

We sit in the heat, the tension building as we all await those beautiful 4 minutes we’d come so far to experience. I sit anxiously in my lawn chair, sucking down a cigarette as the band plays the last song of the album, Eclipse. Bombastic cymbals crash through the wailing vocals vibrating through the air from the massive amplifiers on stage as the band plays their final riff.

And everything under the sun is in tune

But the sun is eclipsed by the moon

Around 1:30 p.m.

“Shake, shake from the shoulders, and we are ready to breathe. So, find a comfortable position . . . and just connect into your breath and to sensations, so we can embody that beautiful event.”

A yogi has taken the stage to help the crowd connect with the earth as the partial phase of the eclipse begins. Camryn slides some mylar glasses over my face as I lay in the grass trying my hardest to allow the breath to flow effortlessly into my lungs.

“I am still. And I know. I am here. I am still. And I know. I am here.” The yogi’s mantra rings in my ears as I open my eyes to a tiny black dot working its way into the west side of the sun. Even during the partial phase, it seems to wrack the mind. The sun simply isn’t supposed to look like that. An orb the size of 109 Earths shouldn’t be covered up by something as small as the moon. Every day, the sun is there. And then one day, if only for a couple of hours, it slowly gets eaten away by a tiny celestial body only 1/400th of its size. “I am still. And I know. I am here.”

3:00 p.m.

The earth has gone cold, a breeze blows gently through the field as the sky continuously darkens to the point of dusk. A soft yellow radiance encompasses the horizon, fading into deep blue as it rises toward the sky. A shiver creeps through us all starting at the skin and traveling up the spine straight into the brain.

Minutes feel like seconds. The tiny slice of the sun that remains disappears through the mylar glasses. The crowd erupts into animalistic howls, cheers, and bellows that shake the air and spark something in me that I’ve never quite felt before. I remove the glasses.

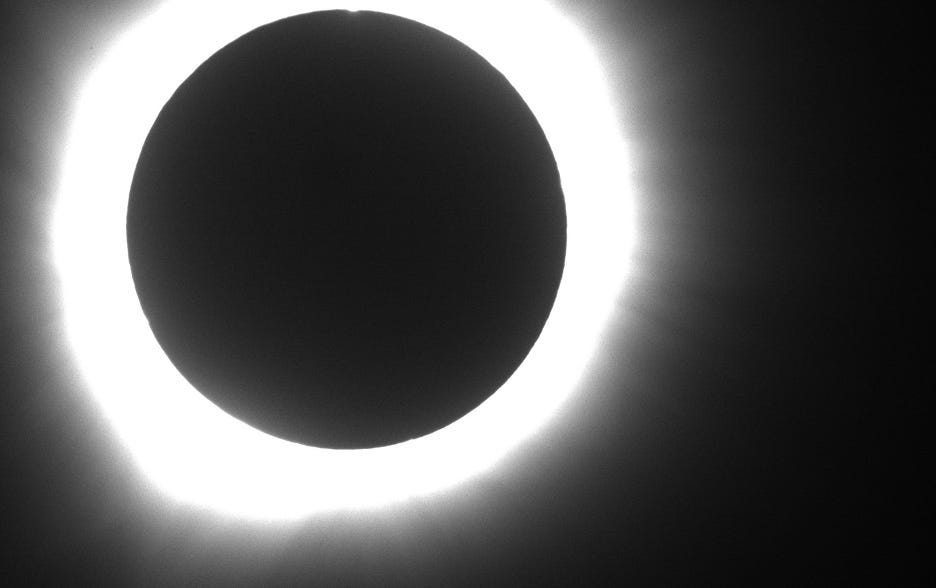

It’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. A black void watches over us where the sun should be, the corona is all that can make it past, enveloping the void in a seemingly impossible glow. A small purple flare dances back and forth along the bottom of the void. It seems as if I could just reach out and touch it.

My jaw drops and I slowly fall to my knees.

“I get it. I finally get it,” I say. Camryn laughs behind me.

The local wildlife joins in the praise of the phenomenon, chirping and ribbiting along with our howls in the false night. Jupiter and Venus even make an appearance in the sky to join in on the worship.

And just like that, the void bows out of the way, unleashing the sun’s blinding light back onto us.

It’s difficult to describe the feeling in the air after those 4 minutes of awe. There’s something about a shared event like an eclipse that can bring hundreds of perfect strangers to know each other like brothers and sisters. People hug, people high-five, they join hands and shout into the sky.

In the post-totality chaos, I run into a man named Marco Cimmino, who’d been chasing totality for just over 20 years.

“This is my third eclipse, but something always fucked up and they were always at 80 or 90 percent. In 1999, I was in France to see one there, but I missed it by probably 30 kilometers,” Marco says. “And then in 2017, I was in Portland again we were about 30 kilometers away and I missed it again.”

The third time, he told himself that he’d screwed it up twice, and he wasn’t going to do it again. So, just to be sure he’d see totality in all its true glory, he traveled all the way from San Diego to Loesch Farm, which lies less than one kilometer away from the center of the eclipse’s path. Marco shakes his head and glances up at the sky.

“This is my dream coming true,” he says.

We hug and shake hands with all our cosmic friends and head toward the car. As we walk I glance through the mylar glasses back at the sun. About half the sun is exposed in the sky. The show may be over, but the thrill remains forever.

Why do people chase eclipses? For some, it’s a chance to throw a party. For others, it’s about capturing a celestial phenomenon. To some people, it’s as simple as breaking away from the mundane—experiencing everything that life has to offer, while to one man it’s about fulfilling a lifelong dream. Why do some people chase eclipses? I finally get it.